Striving for a World Without Bars

All over the world, increasing numbers of people are spending increasingly long periods in prison. But excessive use of prison as a punishment does not lead to a better society, argues writer and professor Peter Vermeersch, but merely to an excessively large prison industry. How can it be changed? His experience as a jury member in a criminal trial led Vermeersch to delve into alternatives to imprisonment, and to discover a world that was far removed from naïve dreams or bizarre utopias.

In 2016 I spent about ten days as a jury member in a criminal trial. The days were long. Brussels was enjoying an early spring while I sat in a gloomy courtroom in the Palace of Justice together with eleven other jury members viewing PowerPoint pictures of an autopsy and listening to experts being interrogated. In the evening, I would go back to my hotel room alone and lie on my bed deep in thought.

Viewed juridically, it was a fairly straightforward case of murder. On a rainy November evening, the young man concerned, with two underage accomplices, broke into the apartment of an elderly woman. They had stolen money, the woman had resisted, and the situation descended into chaos. The events could have been taken from the script of a cheap whodunnit: urban desolation, youthful immigrants, a shy, elderly widow left alone to die of her wounds.

I was reminded of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, except this was not fiction

I was reminded of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, that seminal account of senseless robbery and murder. Except that this was not fiction. From the cross-examination I had tried to piece together a picture of the actual life of the accused. I caught glimpses of a youth in trouble with the law, possible parental abuse, and at least one attempt at suicide at school. How was one supposed to judge? I tried hard not to think of the approaching and irrevocable moment of judgement, when I and my fellow jury members would have to declare ourselves.

On the last day of the trial, late in the evening after our deliberations were over, the judge sentenced the accused to twenty-one years detention. Twenty-one years for a man aged twenty-one. He was handcuffed and taken off to the Van Vorst prison, the place from where he had been brought that morning but to which he would now return in a different guise: no longer the accused but the convicted. Nevertheless, he was still the same gawk whom we had seen ten days earlier entering the courtroom, an inarticulate, awkward lad who in one incomprehensible moment had not only taken someone else’s life but had also utterly destroyed his own for a couple of hundred euros and some drug-induced kicks. Was he a monster? It is unlikely. But what could one really know about the rest of his life? In the courtroom we were only shown ‘the facts’, or a few snatches of them, those few certainties that would suffice to lock him away.

The trial was over, and I was overcome by an unpleasant mixture of emotions. I had the impression that this was just a beginning and although I would not be playing any role in its future development, I experienced an overwhelming urge to keep track of it in detail. What would he do with the rest of his life? Could he do anything with it? Would he be able to do anything for his victim’s relatives or for society at large that could in some way make up for the inhuman harm that he had inflicted? Was it possible to prevent him from being drawn more deeply into crime? It was not remotely a part of a jury member’s responsibilities, but it continued to bother me. Doors were closed: those of the courtroom, those of the prison cell. I stood in the street, he was stuck inside, and that was that. That’s how it goes. He had destroyed and therefore we had to destroy him. The punishment was to add yet more pain to the already existing pain. I felt that I was part of an institution that inflicts pain.

I felt that I was part of an institution that inflicts pain

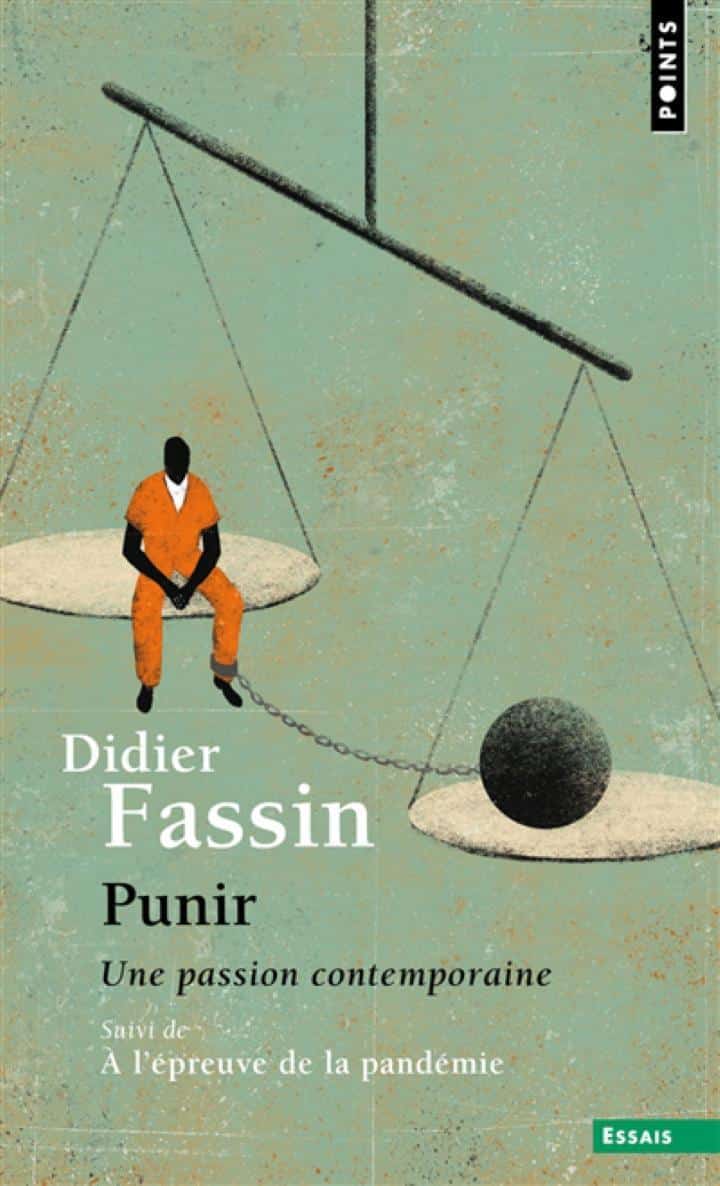

During the lonely evenings in that hotel room, I had read Punir. Une passion contemporaine by the French anthropologist Didier Fassin. It was about the history of punishment. About imprisonment as a modern invention. Anyone who thinks that there have always been prisons is mistaken. Equally mistaken are those who think that it is an effective cure for criminality.

In his book, Fassin explores the spectacular increase in the number of detainees in many countries (over 10 million worldwide in 2018, a rise of about 25% from the year 2000) – especially in the United States (comfortably leading the world with 2.1 million) and in France (about 65,000), but also in Belgium (about 10,000).He discusses those who have ended up behind bars: the makeup of the prison population tells us much about how a society’s system of punishment functions. Put another way, it is chiefly the poor and disadvantaged who end up in jail (in the USA blacks in particular). He cites research that repeatedly shows that more and longer punishments do not reduce recidivism and that robbing people of their liberty brings about in practice even more suffering in the form of loneliness, sickness, and exposure to yet more criminality. Are these simply extra punishments that one must just accept? In any case it was clear that imprisonment didn’t help. In fact, as a punishment it helped nobody – neither the detainees nor society, and certainly not the victims’ families. Their situation, their traumas, how to resume their lives, all those problems conveniently disappeared from the picture.

Fassin concludes his book with a question. Punishment can perhaps be justified if it solves a problem, if it corrects a fault, reforms the guilty, protects society or repairs the social fabric. But if detention achieves none of those things, but instead undermines society, is it not time to urgently consider adopting a different approach?

The hotel bed had been soft, but I hadn’t slept well. I had fulfilled my duty as a citizen, but had I acted humanely? And did being humane mean opting for exemption from punishment? That also seemed absurd. Nevertheless, I was fairly certain that it was naïve to expect prison sentences to produce anything good or humane. Rather the opposite. Detention was a solution that solved nothing. It was something that we resort to because we can think of nothing better.

I had fulfilled my duty as a citizen, but had I acted humanely?

Even the news bulletins in the week of the trial did little to calm my moral unease. It was precisely at that time that yet another prison crisis erupted in Belgium, with prison staff on strike and alarming reports in the press of overcrowding in buildings in a lamentable condition, some of them nineteenth-century structures that were literally crumbling. At the end of 2016, the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture of the Council of Europe published a report that concluded that a red line had definitely been overstepped. Spectacle de désolation totale, total desolation, wrote Le Monde in an article on conditions in Belgian prisons. ‘Pooing into a bucket next to the rats’, was the headline in the Dutch NRC newspaper.

Repentance through imprisonment

The issue would not leave me. I was able to write off my experience as a jury member, but that did nothing to calm my uneasiness (or whatever it was. An urge to know more? Fascination? Research interest?). If the time had come for a new approach to prisons, where were we now? Had we stopped thinking altogether? Was there still an ideal that we were aiming for? I began to read more widely in the field of prison studies.

There I discovered that since the birth of the modern prison (roughly the end of the eighteenth century) there has been no shortage of ideas about how prisons might be improved. Of course, not all have been a resounding success. The best-known utopian vision was that of the English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1842). He envisioned a building that would be useful and efficient, a dome-shaped prison with a central watchtower, in which the cells were built on various balconies around a circular track. A person in the watchtower could keep everyone under observation, and the awareness of ‘being seen’ was supposed to make the prisoner a better person.

In Bentham’s inspection house the removal of liberty would encourage a change of behaviour. It was ‘a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind’. There was only one problem. In the case of the pure Benthamite prison, of which very few were built (the old prisons in Arnhem, Breda and Haarlem came the closest), the effect was disastrous. The inmates, locked up in total solitary confinement and under constant observation, became utterly paranoid and suffered nervous breakdowns.

Edouard Ducpétiaux

Edouard Ducpétiaux© Wikimedia Commons

Belgium also had a well-known prison reformer in the nineteenth century. Edouard Ducpétiaux (1804-1868), as inspector-general of Belgian prisons, campaigned for many years for a holistic system of ‘separate imprisonment’, in individual cells, and his ideas inspired a whole generation of prison architects. It was believed that this kind of imprisonment would lead the detainee to repentance. Imprisonment would then itself become a form of improvement.

Even today, reforms often have much the same goals. Their aim is still to bring about behavioural change outside

mainstream society, even if in more humane circumstances. The view of the environment in which behavioural change can occur has now changed: the buildings should be more practical, more transparent and less intimidating. This can be seen, for instance, in the plans for the prison in Haren soon to be the largest in Belgium (1,190 prisoners) and which, according to its website, will become a ‘village’ with ‘lifestyles taken from normal everyday life’. Present-day prisons do not expect repentance through segregation, but aim rather at resocialisation through connections, such as cultural group activities: drama and reading groups, pop concerts or cooking pancakes. The ideal is Halden Fengsel in Norway, where detainees can go jogging out of doors, play music in a studio and follow courses in cooking. Is that then the utopia towards which we should be striving?

Street art by Dolk in the Norwegian model prison Halden Fengsel

Street art by Dolk in the Norwegian model prison Halden Fengsel© Wikimedia Commons

To discuss this with experienced Belgian experts I visited Leuven Central Prison, once the most progressive prison in the country (the building dates from 1860 and for Ducpétiaux it was a model prison), and now a place where helpers and volunteers try to kindle social connectedness through reading groups, courses and concerts. If there was one place where the old ideal and the new might be seen together, it would surely be there.

I certainly saw the old: the barred windows, the gigantic bunches of keys, the old-fashioned tiled floor, the reinforced cell doors in their rounded frames, the high walkways with gothic windows at the end of each wing – all vintage Ducpétiaux.

Leuven Central Prison, according to Ducpétiaux a model prison

Leuven Central Prison, according to Ducpétiaux a model prison© Wikimedia Commons / Sally V

In the small theatre, twelve chairs were set out (the number was accidental, but striking: first 12 jurors, now 12 prisoners). I sat down when they came in. A man wearing a red sports jacket approached slowly, he had a white stick with which he tapped my foot, and then stuck out his hand. Then the others gave me a hand and sat down.

I find it hard to summarise the conversations that ensued, but I remember being gripped by the various life stories that rose to the surface. C., the blind man, talked about family members, who are so often forgotten, including those of the perpetrators. They often feel rejected and thereby in effect also being punished.

I heard their stories and observed their regrets, their sense of injustice, their struggles and their anger. They spoke about the court that had sentenced them, their daily concerns, the work, the administration, the mindset that was needed just to survive, the strikes, the politics, their own conflicts and how they resolved them. And they would always return to that one single event: the reason they were there. They had inflicted great harm.

As prisoners, their main concern was to survive in the world of the prison as it was

Although I raised the question of prison reform, I was struck by the fact that ultimately these prisoners had little to say on how the prison might be changed. They recounted personal, complicated and tragic stories from their own lives, but when it came to the prison itself they remained trapped within its own logic. Or they focused on details such as the washroom windows rattling in the wind. As prisoners, their main concern was to survive in the world of the prison as it was. It seemed that all the rest – making a fresh start in society, learning to live with guilt, rebuilding one’s life – would assume importance only after leaving the prison.

Critics of Belgian prisons should not focus on the tiles, the gothic style and the windows in the washroom that don’t close properly. But rather on the essentials: being locked up in cells, time as punishment, a controlled existence in a specified place, physical disciplining and isolation, the belief that this will help in some way. Even a technologically advanced, well-lit and energy-efficient prison will not differ fundamentally from a nineteenth-century prison if it continues to operate on the old assumption that punishment is the route to improvement. That is possibly the real legacy of the present prison system: a questionable belief that everyone accepts as true and which is therefore constantly being renovated in its original form.

That is what I took from those conversations. But not only that. Right at the end of that prison visit, a muscular fellow with a peaked cap spoke about a conversation he had had with the younger sister of his girlfriend. A monitored conversation between an inmate and a relation of the victim. It was a bizarre conversation because the sister was the spitting image of his girlfriend, whom he had murdered in a fit of rage when he caught her with another man. It had resulted in no girlfriend and twenty-four years in prison. And then that conversation with the younger sister, which was almost as if he were talking to her again. ‘I can never forgive you’, she had told him. He had replied: ‘I understand that. I just want to explain how it happened, because I never wanted it to happen that way.’ She cried; he cried; and even the two officers in attendance cried.

The fragmented prison

Excessive use of imprisonment as a punishment does not lead to a better society, but only to an exorbitant prison industry. But what is the alternative? Have prisons a future? Can we do without them?

It is not easy to discuss these questions calmly yet frankly, let alone debate them in public. Firmly held views keep getting in the way. We assume that prisons are only populated by monsters. We assume that our anger will only cool if we retaliate. We believe that the harm we have suffered can only be eased if we ourselves inflict harm.

So, a wider social debate is not easy, but nevertheless very necessary. Where then should one start? Perhaps with examples that show what is possible and what has already succeeded elsewhere.

Prison reformer Hans Claus: 'A uniform approach can never be the correct solution. Attention to the individual is much more important'

The De Huizen (The Houses) scheme in Oudenaarde organises detention differently, in smaller detention houses, with an emphasis on resocialisation. Hans Claus, the best-known promoter of this idea writes in his inspirational book Achter Tralies (Behind Bars): “A uniform approach can never be the right solution. Attention to the individual is much more important.” Claus puts it vividly when he says that we should ‘crumble’ our prisons, break them down into smaller units. Detention works better in smaller centres, organised within the community, and supported by well thought-out programmes of guidance and reclassification. The inmates are given the chance to feel part of the wider social fabric which continues to function normally outside in the street, the city, and the world. There is still security and surveillance, but these are not prisons and should not be given that name which implies a form of retribution. This is different: they are houses.

This not only raises the question of how to deal with different crimes in different ways, but also how to abandon the whole notion of prison. To be able to talk of a future without prisons, we must expand the horizons of our imagination, argues Phil Crockett Thomas of Glasgow University. She invites people to do just that. What would a world without bars look like? Use your imagination! She calls this novel approach ‘Fictioning’ and the name of her project is ‘Prison Break’.

What does world without bars look like? Use your imagination!

This is also what prison abolitionists are striving for. Anyone who takes the trouble to read the research will not find some naïve dream world full of bizarre utopias. Here too there is diversification of institutions and resocialisation. But more especially, there is a view that extends beyond the individual or interpersonal aspects of a crime. Criminality concerns all of us; it is not confined to specific individuals who can be locked safely away behind walls. It is a problem within society, and society should therefore face up to it.

Another example of what is already happening is getting victims and perpetrators to talk to each other. This often goes by the name of restorative justice although it does not necessarily involve restoring or repairing the damage inflicted by the crime. It does, however, involve a change in the relationship between those involved – as a victim, as a perpetrator, as a neighbour. There is much that can be done at that level: recognising the anger and misery, allowing some level of trust to grow, realising that in spite of everything life can at some point be resumed. That will only happen if the guilty person is seen as someone whose intrinsic worth can be acknowledged by the victim, rather than only being seen as someone who destroys.

Thinking about a future without prisons requires one to think in particular about the future of society outside the prison, about how society views criminality and structural injustice, and how these issues should be dealt with.

A less punitive society starts with people who have the courage to take an active part in the process themselves

A less punitive society must begin with those who do not automatically expect conflicts to be resolved by a formal system of punishment that takes over and deals with everything, but who have the courage to take part in the process themselves. Look others in the eye, talk with them, listen, experience the chaos of human interaction, actually face up to conflict and try to make something of it. ‘Justice begins’, wrote Howard Zehr one of the pioneers of restorative justice, ‘with a concern for victims and their needs. It seeks to repair the harm as much as possible, both concretely and symbolically.’

That is very different from an institution that inflicts pain. Concern for the victims and their needs provides a good basis on which to build for the future.